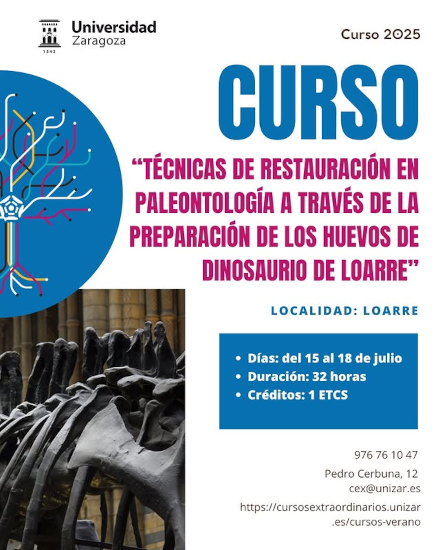

I woke up around 7:30. After I had stressed out so much about reaching there, I almost could not believe I was really in Loarre, at the feet of the Pyrenees mountain range. I lounged around until breakfast started at 8:30. I went down and the choice was limited but adequate – fresh bread (still warm, the bakery was literally under my window, and it had been making me hungry for an hour), tomato spread, Spanish omelette, cheese, sausages, pastries, coffee, milk, and an assortment of jams and butter. The coffee was weak, so I had a couple of cups, but the orange juice was freshly squeezed and awesome. I made myself toast with cheese and omelette, loaded up on the caffeine and went on my way. At 8:58 I was at the museum-lab Laboratorio Paleontológico de Loarre (Oodinolab). And there was my name, on the attendance sheet for the course Técnicas de restauración en paleontología a través de la preparación de los huevos de dinosaurio de Loarre: Palaeontological Restoration Techniques through the preparation of Loarre dinosaur eggs. Everything was going to be all right. I have to admit I was 100% ready to show all my emails and confirmation should any problem have arisen… but it was all right (which… I should have known due to the email received previously… but I am an overthinker by nature).

After signing attendance and checking details for the certificate, we received a tote bag with postcards, notebooks and pens. The course started with a welcome and introduction by Miguel Moreno Azanza, who is the Universidad de Zaragoza researcher in charge of the lab. The most important goal of the course, he transmitted, was empowering us with knowledge about every step involved in fossil-handling: from digging to commercial exploitation, including geology, conservation, restoration, study and museumification.

The course kicked off with the guided visit of the museum-lab that is usually done for kids and families, including pulling out crates for our backpacks. Thus we learnt about the story of the discovery of the eggs – a fellow researcher of Moreno Azanza’s, José Manuel Gasca, a geologist, runs mountain trail. In 2019, he was training with a few colleagues when during a break he looked at the ground and saw what it looked like a fossilised dinosaur egg. And that is how one of the largest egg-dinosaur sites in Europe was discovered.

From the science standpoint, we also heard about how hardshell eggs played a key part in the evolution of animals coming out of the sea, as they allowed reproduction on land, without having to return to water. There were (are) different strategies to take care of eggs, and spherical eggs mean that they were (are) buried. From fossil tracks, we know that the dinosaur females that laid their eggs in the area buried them for protection using their back legs. We saw two cast jackets too, ready for research, on display.

Fossil eggs are categorised as oospecies, unless or until it can be proven which animal laid them. The Loarre dinosaur eggs are tentatively classified as Megaloolithus siruguei (sometimes spelt Megaloolithus sirugei), laid by a species of titanosaurian sauropod – some candidates are Garrigatitan, Ampelosaurus and Lohuecotitan. Sauropods were plant-eating dinosaurs that moved on four straight legs, and had long necks and tails, such as Dippy, the Diplodocus (and other copies, such as the one in Madrid or Paris). During the Cretaceous period, the dominant group of sauropods were the Titanosaurs, the last surviving long-necked dinosaurs until the extinction of dinosaurs – in South America there was Patagotitan; another example is Qunkasaura pintiquiniestra, which I saw in MUPA and MARPA exhibits.

The first dinosaur eggs ever registered were found in the Pyrenees – on the French side though – by Pierre Philippe Émile Matheron in 1846, and described in 1859 by Jean-Jacques Pouech. In 1967, Pierre Souquet documented dinosaur eggshells around the reservoir La Peña, some ten-ish kilometres from Loarre (had I known in 2021…). These were the same oospecies as the ones in Loarre – since the fossil layer is the same, it makes sense.

We were supposed to have a video-conference inauguration with someone from the university, but she decided to come in person, and that was moved to 19:00. So instead we hopped onto the vans that the organisation had provided and drove towards the geological formation called Mallos de Riglos, in the village of Riglos (hence the obvious name). The Mallos are a number of vertical domes conformed by reddish conglomerates. I had actually seen these geological structures before, from the other side of the River Río Gállego – not up close. The wording of the email “a slight ascent” had not made me suspect at first we were going to climb all the way up in the heat. Looking back, it was not that bad but a) I was not mentally prepared for it, and b) I have a new backpack, and it’s comfortable but… differently-shaped, so my centre of gravity was all off. There, Lope Ezquerro Ruiz (honourable mention to Manuel Pérez Pueyo, who cracked jokes and held the whiteboard) gave us a few good pointers on geology which made me wonder where he was when I was first studying geology at university.

Simply put, if one assumes that the natural laws have not changed with time (Uniformitarianism), then three things happen that define geology: strata deposits are horizontal, deeper strata are always older, and if they are not, it is because something new has eroded or deformed them. Of course, the Pyrenees mountain range is anything but flat.

On site, we learnt about the Garum facies, the result of the sedimentation of fluvial and marshy red clays. The layer started forming during the Maastrichtian (the latest age of the Upper Cretaceous, 72.2 to 66 million years ago. Both the Maastrichtian and the Cretaceous ended with a literal bang – the Cretaceous–Palaeogene extinction event, when non-avian dinosaurs went extinct, marked by the K-Pg boundary (formerly K-T boundary), a layer of sediment rich in iridium which probably came from a meteorite impact. The deposit of Garum facies continued through the first age of the Paleocene, the Danian. This means that the K-Pg boundary is somewhere inside the layer, which is pretty cool. And even cooler? There are dinosaur eggs there, obviously from before the mass extinction.

We learnt about this literally standing on the Garum itself. We talked about the time when the a lot of the Iberian Peninsula was a shallow sea with scattered islands, and then sat to try and “see” the processes of folding, faulting and erosion that created the Pyrenees mountain range as the African tectonic plate pushed against the Eurasian plate.

Every now and then, a vulture flew above us, in wide circles. We were apparently not appetising, because it flew away every time. Once we tackled the descent, we headed towards Ayerbe, where we split up for lunch. At 16:00 we met up again so professor Lope Ezquerro Ruiz could demonstrate how strata bend and break using a model and sand. Afterwards, we drove back to Loarre.

In the modern town hall, we had the first lecture of the afternoon, by José Luis Barco, Manager of the business Paleoymas, a company specialised in protection, development, management and use of cultural and environmental assets, with a strong emphasis on palaeontology and geology. One of their work lines is monetising projects related to palaeontology, as opposed to the “research-focused” stereotype. Between a palaeontological discovery and its communication or exploitation for the general public, there is a gap that can last over a decade.

Paleoymas is responsible for the project Paleolocal, which created the museum-lab in town, with the idea of studying the fossil eggs almost in situ, which would develop a touristic resource and help the village profit from it. The museum-lab is technically part of the Natural Science Museum Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Zaragoza, which has custody of the fossils according to the regional law. However, keeping the eggs in Loarre is a way to involve the community into protecting the palaeontological site, as well as to create a tourist flow to the village itself. See: yours truly, who spent 240 € in lodging there.

The second lecture was given by Miguel Moreno Azanza, who talked about the Theory of Excavating a Palaeontological Site, as one of the activities in the course was working on the field. The summary could be: “forget Alan Grant with a paintbrush, think hydraulic hammer”, but the important lesson is “do not dig up anything you cannot take with you, and register any and everything you see / do / touch”. Also, regarding egg shells, it’s important to write down whether you find them concave up or concave down. This can help decipher whether the egg has rolled or not (for example, if several eggs are found together, were they in a nest, or where they moved there somehow? Did a baby dinosaur break the eggshell?).

Around 19:30, we had the official inauguration of the course, with a representative from the university, Begoña Pérez, and the mayor of Loarre, Roberto Orós, who was nice enough to buy us all a drink afterwards. Not one to turn down a free Coke, I tagged along for a while, and when people started taking their leaves, I returned to my room. I had some crisps in lieu of dinner, took a long (and I mean long) shower, scribbled down some notes and lay down till it was time to sleep.