Due to the amount of near-misses, I had started thinking about this as the luckiest unlucky trip in a long time. Unfortunately, this was the day the luck ran out. As I woke up and turned on the phone I received the notification that the cable-car to go up Mount Teide was closed due to bad weather, which was a bit of a blow. I mean, I was in the middle of the natural park, without anything to do within a couple of hours by car as the hiking trails are closed on Monday mornings as it is then when the mouflon population is controlled – using rifles. I did not want to end up shot.

If you consider that the island Tenerife is one big volcano, Mount Teide is the most famous eruptive fissure. Considering it an independent item, it is a stratovolcano. The cone stands around 7500 metres from the sea floor, with an emerged 3715 m above sea level. Its base is located on a previous crater called Las Cañadas. Mount Teide last erupted in 1909, so it is still considered an active volcano, and it hosts a bunch of towns on its slopes, that might get obliterated in an eruption. Aside from being a National Park, the area is a Unesco World Heritage Site.

Historically, an eruption was reported by Christopher Columbus in 1492. Most recent eruptions happened in 2805, 1798 and 1909. Looking back, Mount Teide formed around 160,000 years ago, after the collapse of Las Cañadas. The last summit eruption happened in the 9th century, which caused the black lava blocks that seem to run down the slopes.

The whole point of my being there was going up the mountain, so I resolved to try and do that. I knew there was little chance I could make it to the top even with the access permission, but I would try. I decided to gamble the track Sendero de Montaña Blanca, which is the most typical one. For this, I had a good breakfast and started walking around 9:45 am. The track runs 8 km and starts at an altitude from 2348 m. If you have the permission, you can access the track Sendero de Telesforo Bravo that peaks the volcano at 3718 metres.

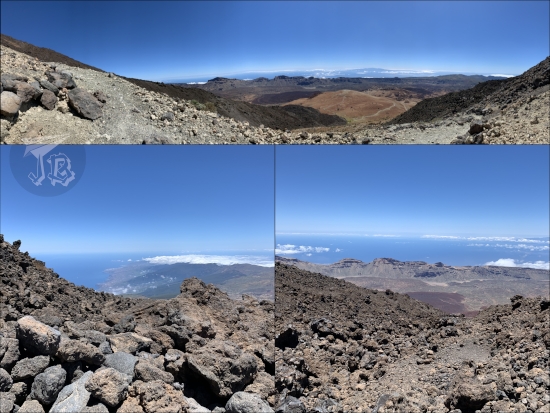

The first part of the morning, I spent on Montaña Blanca. I hiked around 3 km upwards in an hour or so. A park ranger told me that the bad weather was actually strong winds and to be careful. I’d never hiked with wind, so I decided that I would not do anything stupid. As I walked, I went by the accretion balls affectionately called “Teide Eggs” Huevos del Teide.

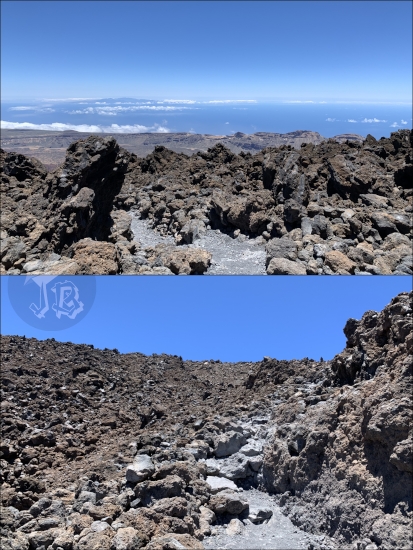

Eventually, I reached the actual foot of Mount Teide, and this is when things got hard – and spectacular. The slope became much steeper and the wind made it hard to move forward. I walked between the two dark petrified lava flows, and could see Montaña Blanca and the Atlantic Ocean beneath.

I reached Refugio de Altavista at 3260 m around 14:00. At this point I was two kilometres away from the next station and 650 m away from the crater. Unfortunately, the elevation was still around 500 m. At this point the wind was very strong and shortly after the refuge I saw an area of the slope I knew I could climb up… but I knew I wouldn’t climb down with such strong wind, not safely. So I realised I had to turn back, even if that meant I wouldn’t see the peak, much less reach it. However, it was the sane thing to do.

It took me two and a half hours to hike down, and I made it back at the Parador around 17:30. I had a shower and I felt tired, though not as sore as I imagined. For dinner, I tried some local speciality “wrinkled potatoes” papas arrugadas, which are boiled in saltwater, and they are so high-class that can be eaten without being peeled. They come with some dips, a bit too spicy for my taste, but they were delicious.

I was a bit bummed that I did not manage to reach the crater, but I think I did a good job, almost 1000 metres up and down. I guess it just meant I had to go back at some point…