I had made a thing out of two coffees for breakfast, and today was no exception. The whole group was now in the hotel so we were ready to go see the sights. The bus had barely hit the road when our guide gave us a huge grin and decalred “I’m the first Turkish face you meet during this trip. Trust me. We’re going on the balloon is too expensive, so we’re not gonna do it here. We’re going to do it somewhere else”.

I was crushed at these words. Had he said this the previous day, I would have arranged to go onto the balloon on my own – today. Now, with a 5:00 departure time the following day, it was impossible. I don’t have words to write how I felt – devastated, cheated, furious. The option to ride a balloon in Cappadocia was in the documentation, and I had budgeted for it. And this guy had plain and simply… robbed me from it, because he did not want to wake up early after picking the other half of the group from the airport. Looking back, I should have tried to do it myself, hiring the flight on the hotel for today – and knowing that does not make it any better, because I could not do this one activity, which was important for me, not because of the weather or any actual problem. Just because the guide did not want to do his job. I did try to get him to reconsider, but he was like “no can do”.

Thus, I reached the conclusion that the travel agency, Oxin Travel and the guide himself sucked. Through the day (and the rest of the trip), I would build evidence on this – such as hearing explanations that did not make sense, or just contradicted what was written on the panels. I’m surprised it did not cross my mind to leave the trip at that time, because I was seething and heartbroken. In the past, I have tried to leave unsavoury experiences out of JBinnacle, but this would not be an honest trip report without all the emotions that coursed through me during that day – and to be honest, this was just the beginning of the problems. I wrote an email to the distributor that very same day, told the guide, and have complained formally to my travel agent. I have no hope for any solution, but at least I made it known that I was not happy with the services provided. And this trip was not cheap, at all.

I had to try to get over the disappointment in order to at least see what I could of the region. It was hard, I felt a cloud over my head ruining the mood. I almost did not care about anything else, but I knew I had to make do with what I had, or let my whole trip be ruined. Thus, I tried to get myself into the right mindframe to enjoy the World Heritage Site Göreme National Park and the Rock Sites of Cappadocia as much as I could.

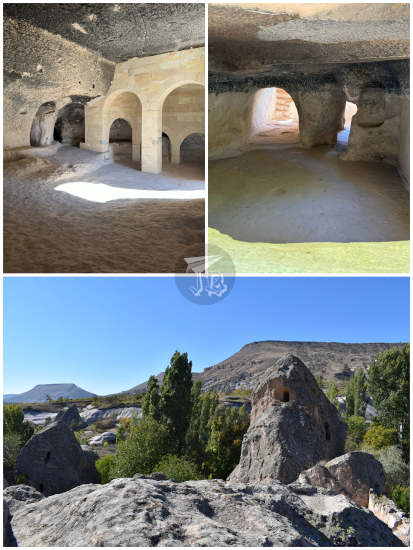

Around 9:00, we reached Christian Keşlik Monastery Keşlik Manastırı outside the town of Ürgüp, which is a cave monastery. Human history in Cappadocia is tied to its geology. Tuff is easy to carve, and a lot of civilisations have made their dwellings into the earth instead of on it. First, it was the cavemen, and much, much later the Christians. The first buildings from the monastery date back from the 3rd century CE. Between the 1st and the end of the 4th centuries CE, Christianity spread through the Roman Empire, coming into conflict with the established religion, which deified the Emperor. As Christianity forbade idolatry, their refusal to adore the Emperor as a god made them a target of persecution, accused of treason. In some Roma cities, the Christians took to the catacombs. In Cappadocia, they dug cave monasteries.

Within the tuff structures, ancient Christians created all the items that one would find in a regular monastery – a church, two actually, St. Michael and St. Stephen, a refectory, a winery, dwellings, a baptistery created from a sacred spring… The monks could perform their rituals and protect themselves from any possible attack. It was a functioning Orthodox church well into the 20th century.

The most important cave-building in the rock is the Church of Saint Michael. Its ceilings are decorated with black backgrounds and colourful figures, although many were damaged by iconoclast movements. There were also tomb-like structures where the monks meditated. Underneath the church, there is a baptistery, and next to it the refectory, with a long table and seats carved out of rock. Outside, you can wander around the dwellings, halfway between caves and houses, which served as rooms for the monks.

Afterwards, we headed out to the Underground City of Mazi Mazı Yeraltı Şehri, known in the past as Mataza. There are between 150 and 200 known “underground cities” in Cappadocia. They were initially carved between the 8th and 7th century BCE by the tribes which dwelt in the area. Turf is easy to carve and there is no water in the soil, which made it easy for the tribes to dig “caves” under their houses. These caves became “rooms” which ended up connected to one another through tunnels. As time passed, the cities became more and more complex, with decoy tunnels and booby-traps that the locals could use to hide, safeguard their resources, and protect themselves from raids.

The cities were layered, and the levels were used for different activities – upper floors were for stables, underneath which stood the wineries and ovens… They had wells and ventilation systems that could not be tampered with by the enemies, and even a communication system to talk to people who were in other rooms. Mazi itself had eight stories, four different concealed entrances, and rounded rocks that could be used to close off the corridors. About 6,000 people could survive in its tunnels for up to a month. We did not have much time to explore as we had to move as a group, but it looked really cool.

We went back onto the bus to head to Guvercinlik Vadisi, Pigeon valley – so called because the geological formations were excavated into dovecotes, since pigeons were used for food and their droppings as fertiliser. As we had 20 minutes there, I could hike down into the valley for a bit and even step into one of the dovecotes. Since it has become a tourist spot, locals have decorated trees with Turkish amulets – evil eye charms – to create photo spots they can request a tip if you get your picture taken there.

Back on the bus, the guide “graciously” and “secretly” stopped at Üçhisar, a town which has turned a lot of its fairy chimneys into hotels and cafeterias. It is dominated by Üçhisar Kalesi, Üçhisar “castle”, the only natural castle in the world, built in a tuff hill.

Then we were taken for lunch, a rather nondescript buffet which ran out cacik (Turkish tzatziki) way too fast, and afterwards to a “jewellery atelier”. The rocks they showed us were pretty, but the jewellery was rather tacky – and their star product? A pendant made of the local semi-precious stone sultanite inside a balloon, so we were not amused. I was not the only one angry about the whole debacle.

During the bus ride the guide had pitched several optional activities, and I decided to take a so-called jeep safari, run by locals, which takes you in a kind of luxury jeep up and close with the geology of the area. I got that one because it was external and better than nothing, but I did not sign up for the “traditional Turkish night of alcohol and dancing” – I don’t drink alcohol and I was not in the mood for dancing.

The jeep safari drivers picked us up from the jewellery shop around 16:00, whilst the rest of the group went back to the hotel. I felt so cheated – six hours in Cappadocia to go back to the hotel at 16:00 is disgraceful. But then again, I was not in my best disposition. Good that I still had the chance to drive right into the heart of the valleys, at least.

It was a pity that the drivers spoke zero English or Spanish, because it made it impossible to determine where exactly he was taking us. However, we got close to the rock-houses, saw the valleys, the castle, and finally, finally, finally got close to a fairy chimney! We even caught a glimpse of one of the volcanoes responsible for the landscape. It was hard having to go back to the hotel at sunset, but I had a lot of fun – I shared the car with a couple, and the poor lady was terrified by the driver’s antics. I was honestly more worried about the times on the road than the bouncing through the trails.

However, back in Suhan Cappadocia Hotel & Spa before 18:00 made the sadness hit – and no internet in the rooms did not help for any kind of distraction. I tried to walk around the village to try to see something, but I did not find a way, and it was getting dark. I packed for the next day as we were leaving the area. After dinner, I wrote to the travel agents’ in Spain to complain, with zero hope for a solution as it was a Sunday, but I wanted it out of my system. I spent a really bad night, and it was stupidly short because I could not fall asleep…