There is no reason to doubt the folk / pre-Christian origins of Carnival (Shrovetide). Scholars trace it back to Greek Anthesteria to honour Dyonisius and the Roman Saturnalia – Romans liked adapting everything from everyone after all, especially if a party could be had. It might even be related to Imbolc, an ancient Irish festival celebrated halfway between Winter Solstice and Spring Equinox (similar to how Hallowe’en is the night between Autumn Equinox and Winter Solstice). In the European Middle Ages, it was around this time when people consumed all the meat they had from the winter slaughter before it went bad – and then they would have no “good” food for a while. This eventually led to the idea of fasting during Lent, when the Christian church decided to hijack the celebrations.

A lot of what we consider “Carnival” today can be traced back to Medieval Italy – it started the masquerade balls, dressing up, and the carnal parades. The most important event was the Carnival of Venice. From there, it spread into Europe and with the Spanish and Portuguese empires to the Caribbean and Latin America.

Going back to its origins, it seems clear that the celebrations were rooted in nature, especially the coming of spring. Just as Hallowe’en marks the beginning of winter, it is around Imbolc (Christians call it Candlemas, and celebrate it on the 2nd of February) that you start really noticing that the days have grown longer. They are about an hour longer than on the Winter Solstice – at Stonehenge, one of the most natural / mystical points in the world, sunset on the 2nd of February 2024 was at 16:59, while on the Winter Solstice it was 16:02. Like Hallowe’en brings out spirits and monsters, Inbolc starts conjuring spring and nature-related folklore “creatures”.

Looking at Europe, there seem to be a lot of analogous characters in Carnival traditions. The German characters Hooriger Bär (hairy bear) and Strohbär (straw bear) wear a… camouflage / leaves suit covering all its body which looks eerily similar to the English Whittlesea, the Polish niedźwiedź zapustny, the Italian Hermit (tree-man), or even the Slovenian Korant. When one looks at the Korant, it can be seen the “leaves” are actually fur (sheepskin to be precise), which would make it in turn similar to the Hungarian busós, horned and more animal-like. All these appear to represent a connection to nature, only enhanced by the German Hopfennarr, which looks like one would draw a spirit of spring. It would be easy to reach the conclusion that all these characters are indeed related to the advent of spring – both for plants and animals.

As Italy (and especially Venice) made carnival a thing in Medieval Europe, they “exported” the concept of costumes “done right” and “proper” masks. This influenced older characters, giving them a more similar look to the archetypes in the Commedia dell’arte, with colourful clothes and expressive masks. These are more generic, masked, characters as those found in Venice, though in this city every character has its own name and story.

Some of these characters – both newer masked and older nature-linked characters – seem to have their representatives in the current Spanish Carnival folklore. They seem to have been especially important in the centre of the country, more dependent on agriculture and nature cycles than those areas close to the sea. They were popular in the past, and switched from the pagan festival to the Christian one. They were stifled during Franco’s Dictatorship (with the ban on Carnival), and have been recently re-popularised by folklore enthusiasts – some of them have been “rescheduled” to more touristic times than around Carnival. It is considered that the origin of these characters lies in fertility rituals and symbols – such as the orange – and dances from pre-Roman Spain, with some authors daring to call them Neolithic.

I attended the parade Tradicional Desfile de Botargas in Guadalajara which gathered these characters from the town and several other villages in the province. The main and more general name of the characters in this area is botarga. However, there are different characters according to what they look like: botargas, vaquillones, diablos, mascaritas, chocolateros, danzantes, and mascarones. These characters and their recovered traditions were declared Intangible Cultural Asset in 2022. The parade was a big day when most of the characters in the region came together. The parade used to take place on a Thursday before, and it was changed to the Saturday before Carnival so more people could enjoy it.

The term botarga derives from the Italian bottarga, which refers to colourful clothes related to Medieval performances and the Commedia dell’arte (aside from fish roe). The original clothes seem to have taken their name from the 16th-century actor Stefanello Bottarga, who used to wear wide pants, and play one of the archetypical characters, the vecchi (old geezers or masters). Under the name “botarga”, the province has recovered (or reinvented) a few traditions, and up to 36 single characters and groups walked the parade in Guadalajara.

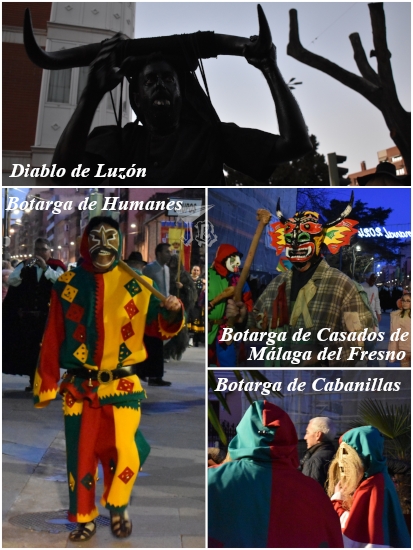

The proper botarga is a usually single character, who wears a mask and garish clothes in bright colours. The masks can be made of many materials, some of them even esparto. The botarga usually carries some kind of staff, and it chases the onlookers, and sometimes pokes them for luck or fertility. Vaquillas (heiferettes) and vaquillones (literally, big male heiferettes) are characters which cover their faces with sackcloth or a similar material; they carry horns, and often cowbells; they represent cattle and are sometimes accompanied by “shepherds” (with staffs – there is a pattern there). The danzantes are dancers, and Diablos means Devils, pretty self-explanatory – some of the latter also wear horns, and a few are covered in black soot, and enjoy “marking” the onlookers with black smudges. Mascaritas and Mascarones both derive from the word mask, and could be translated as “small masks” and “big masks”; the mascaritas are the most common character, usually women in traditional clothes covering their faces with plain white masks.. Finally, the chocolateros or chocolatiers offer the treat (which they… carry in a chamberpot) to whomever they meet – and if they are declined, they use it to “attack” their victim.

There is actually a project called The Botarga Route, with a calendar so one can see each botarga in the original village. Most come out between New Year’s Day and the end of February, but some have been “moved” to the main day of the summer festivals. The great thing about the parade I attended in Guadalajara was that it concentrated a lot of the region’s botargas and further characters, and one “guest” from another region – it was the Desfile de Botargas, Vaquillones, Diablos, Mascaritas, Chocolateros, Danzantes y Mascarones de la Provincia de Guadalajara.

The host botarga, Botarga from Guadalajara (Botarga de Guadalajara) is a team of four. They chase teens and and lightly hit them when they catch them. They play a traditional Carnival game similar to bobbing-for-apples, alhiguí. A dry fig is hung from a sort-of fishing pole, and onlookers can try and catch the fruit – the trick is that one has to use their mouth, not their hands hands. Meanwhile the botargas sing “tothefig, tothefig, not with the hands, yes with the mouth” (alhiguí, alhiguí, con las manos, no, con la boca, sí). Originally, there was only one character that came out on the 17th of January and played alhiguí with the children around the church of Santiago – El Manda (the Order-giver). Later, two more were added – Los Mandaneros (the Order-receivers), and since the custom was recovered in 1998, a new character, Botarguilla (Little Botarga) carries the basket with the figs.

First, all the characters met at Espacio TYCE, then they marched down to the Main Square in front of the town hall Plaza Mayor for the Carnival opening speech, and back.

The host botarga opened the parade. Music was provided by three teams of musicians: Grupo Dulzaineros from Guadalajara, Dulzaineros Pico del Lobo (their main instrument being the dulzaina, an instrument similar to an oboe) and Gaiteros from Villaflores (pipers). Although the parade did not take long to devolve into a lot of chaotic fun, it was organised in three bodies – single botargas, couple botargas, and teams. The signs reading “individual”, “couples” and “teams” were carried by characters wearing full-body costumes that made them look like walking grass-made men. Since I know the town a little, could I watched the parade from three spots, short-cutting from the TYCE area to the square Plaza de Bejanque , and then to Main Street Calle Mayor. Then I walked along towards Plaza Mayor Main Square, where the botargas one by one, or group by group, came on stage as the character was explained.

Aside from the music, there was a very distinctive sound – a lot of the botargas carry cowbells on their belts. The local botargas that participated in the parade are (in alphabetical order of the village they come from, and how they were called onto the stage):

- Botarga de Alarilla: Botarga from Alarilla. It comes out on the 1st of January to greet the new year and send the evil spirits away. When it is not scaring little kids or getting frisky with the single ladies, it gives out little satchels of nuts.

- Botarga de Aleas: Botarga from Aleas. The character used to come out on the 3rd of January, now it comes out on the 15th of August, for the village’s festival. The botarga and a number of dancers go around asking for money and food – especially sweets and wine.

- Botargas y Mascaritas de Almiruete: Botargas and Little Masks from Almiruete. They come out on Shrove Saturday. The botargas throw straw and the mascaritas confetti. There are three other characters – the bear, its trainer, and the heiferette.

- Botarga de Cabanillas del Campo: Botarga from Cabanillas del Campo. The two characters come out on the 3rd of February, sounding bells and cowbells to bother people and summon spring.

- Chocolateros de Cogolludo: Chocolatiers from Cogolludo. They come out on Ash Wednesday to tempt people to break the religious fast. They carry a chamberpot with creamy chocolate, and sponge cakes dipped in it. If they don’t manage to tempt the onlookers, they smear the chocolate on their faces.

- Botarga de Fuencemillán: Botarga from Fuencemillán. On the closest Saturday to the 25th of January, it dances in front of the image of Saint Peter, and chases people to get rid of the bad spirits.

- Vaquillas de Grajanejos: Vaquillas from Grajanejos. They look more like shepherds and farmers than actual cattle.

- Botarga de Hita: Botarga from Hita. Though today the two characters come out during the town’s Medieval festival in July, they are clearly Carnival characters. They represent the struggles of personified Carnival and Lent – though they dress so similarly, I could not tell who’s who.

- Botarga de Humanes: Botarga from Humanes. It comes out on the 1st of January and knocks on doors to wish a happy new year. It wears a colourful costume with 31 tinker bells and seven bells. It blocks entry to the church unless it is given a coin.

- Diablo y Vaquillas de Luzaga: Devil and Heiferettes from Luzaga. Nowadays, they come out on Shrove Saturday. The heiferettes wear red capes, a mask of sackcloths, a hat, and carry bull horns. They toll the cowbells and chase the onlookers. The devil throws straw to symbolise riches and fertility.

- Diablos y Mascaritas de Luzón: Devils and Little Masks from Luzón. The devils carry horns on their heads and cowbells on their waists. They paint their body black and use a piece of potato to feign huge teeth. They “attack” onlookers with a mixture of ash and oil. They are accompanied by the Little Masks, who are safe from their actions, wearing the typical clothing of the area and white face coverings. They come out on Shrove Saturday.

- Botarga de Majaelrayo: Botarga from Majaelrayo. This is one of the characters that comes out “off season”, on the first weekend of September, though the original festival was the third Sunday of January. It is one of the few (if not the only) unmasked ones, and it leads traditional dancing on Sunday.

- Botarga de Casados de Málaga del Fresno: Botarga of Married Couples from Málaga del Fresno. The original botarga came out on the first of January. It stopped for a while and when the tradition was picked up, the festival moved to the 24th of January, and two more masked characters, the mojigangas were added. The botarga carries a staff and a bag of candy and chases people who go and come out from mass.

- Botarga de Mazuecos: Botarga from Mazuecos. On the 23rd of January, they chase the young and hit them with their poles.

- Vaquillas de Membrillera: Heiferettes from Membrillera. They wear two tunics in different colours, a collar of bells, and horns on their waists. They come out on Shrove Saturday to chase the youth.

- Botarga de Mohernando: Botarga from Mohernando. This duo of botarga and buffoon come out on the closest Sunday to the 20th of January. Though they participate on the religious activities in a serious fashion, they chase kids and teens, and play pranks.

- Botarga de Montarrón: Botarga from Montarrón. It comes out around the 20th of January, and panhandles through the village for food and drink that is later consumed by the inhabitants. It is one of the few botargas to attend mass, leaving its bells and mask outside.

- Botarga de Muduex: Botarga from Muduex. This botarga has just been recovered, so it is writing its own tradition. It will come out on the local festival in July.

- Botarga de Peñalver: Botarga from Peñalver. It chases young men and if it caches them, it will ask them a question, and only let them go if it likes the answer. It comes out the first Sunday after the 3rd of February.

- Botarga de Puebla de Beleña: Botarga from Puebla de Beleña. This horned character takes part in the religious ceremonies to honour Saint Blaise (3rd of January) and chases people to hit them with its staff. He also knocks on doors and makes its cowbells toll to call people to mass.

- Botarga de Razbona: Botarga from Razbona. Considered a symbol of prosperity and fertility, it comes out on the closest Saturday to the 25th of January. It picks up donations for charity and cultural acts. It used to attack people who did not cooperate with ash, now it gives out candy for those who donate. However, as it is regarded as a pagan character, it won’t step into the church.

- Botarga de Retiendas: Botarga from Retiendas. It comes out on the closest Sunday to Candlemas. It dances and chases people to the beat of a drum, and takes part in the religious ceremonies.

- Vaquilla de Riba de Saelices: Heiferette from Riba de Saelices. It comes out on Carnival Saturday (though originally it was Shrove Tuesday), charging people and getting mock-stabbed in return.

- Vaquilla de Ribarredonda: Heiferette from Ribarredonda. The heiferette comes out on Shrove Sunday, tolling its cowbells. In the village, shepherds who cover their faces with sackcloth masks keep it in check with their staffs – the person playing the heiferette wears a helmet for protection.

- Botarga de Casados de Robledillo de Mohernando: Botarga of Married Couples from Robledillo de Mohernando. It comes out on the 1st of January and enters the houses to wish a happy new year and wake people up with tolls and chimes from the bells it carries.

- Botarga Infantil de Robledillo de Mohernando: Child Botarga from Robledillo de Mohernando. The only child group in the area, they come out on the closest Sunday to the 24th of January. There is a child botarga, musicians and basket-carriers. They don’t wear masks and they perform traditional dances.

- Vaquillones de Robledillo de Mohernando: Big-Male-Usherettes from Robledillo de Mohernando. Completely clad in sackcloths and carrying horns and cowbells, they charge the onlookers on Shrove Saturday.

- Botarga de Romanones: Botarga from Romanones. They come out on the last Saturday before Carnival (which was technically the day of the parade so… not sure when). The Little Masks throw confetti or flour at the ladies. They are accompanied by a shepherd and a bull – the bull is “fought and killed” a few times, as it can come back to life with a sip of “magic wine”.

- Botarga de Salmerón: Botarga from Salmerón. A group of Little Masks comes out on Shrove Saturday. They throw confetti as a fertility charm. A botarga, Tío Alhiguí (Uncle Tothefig) comes with them to play the game with children.

- Botarga de Taracena: Botarga from Taracena. It comes out on the 23rd of January. Alongside musicians, it walks through the town streets, chasing people towards the church.

- Botarga de Tórtola de Henares: Botarga from Tórtola de Henares. It comes out in the morning of Christmas Eve, knocking on doors for food. It also comes out on the 6th of January and, along the Little Masks, during Carnival.

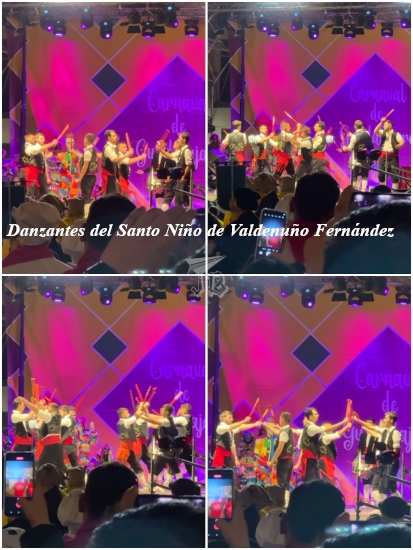

- Botarga y Danzantes del Santo Niño de Valdenuño Fernández: Botarga and Danzantes of the Holy Child from Valdenuño Fernández. They come out the first Sunday after the 6th of January. There are records that a child got lost in 1721 everyone in the village looked for him. The botarga and the dancers recreate this event, and dance in exchange of oranges. One of the dances, the paloteo, involves the group of eight dancers clashing batons with each other.

- Botarga de Valdesaz: Botargas from Valdesaz. This group chases each other and onlookers on Shrove Saturday.

- Vaquillones de Villares de Jadraque: Big-Male-Usherettes from Villares de Jadraque. They come out on Shrove Saturday, wearing orange capes, horns and a hat, chasing anyone they come across.

- Botarga de Villaseca de Uceda: Botarga from Villaseca de Uceda. Recovered in 2023, this botarga comes out the first Saturday after the Epiphany. Its design is modern, and it has mane-looking hair.

- Botarga de Yélamos de Abajo: Botarga from Yélamos de Abajo. It is the only botarga that comes out during Holy Week (Easter) – but it actually looks a bit like a devil. On Spy Wednesday, villagers light a bonfire in front of the church, and summon the botarga with rattles. The botarga uses the bonfire to light its broom, and dances until the broom goes out. On Holy Thursday the botarga is summoned again, and asks for money. The money-giver says a prayer, the botarga kneels and a coin is inserted in the money-box hidden in the botarga’s hump. On Black Saturday, a dummy botarga is burnt in the bonfire.

Furthermore, the four botargas from Guadalajara walked (and ran) after the kids and teenagers at the head of the parade. The Mascarones (Big Masks) from Guadalajara – a cultural association which has worked really hard on the recovery of the botargas – were clad in colourful rags – a lot of them were accompanied by their kids and toddlers in marching suits, with the children handing out candy to both enthusiastic and terrified onlooking kids. The botarga from Muduex, just recovered, received a lot of attention. The kids who were part of the parade often went to give child onlookers candy.

Every year there is a “guest botarga” in the parade. In 2024, the guests are the Hamarrachos de Navalacruz, a group of very druidic-like characters, preceded by their very own flagpole. Navalacruz is a village in the Ávila region, and they have a whole party of creatures – three types: the ones covered in oak leaves, the ones covered in a hay sack, and the ones covered in fur. They seem to represent ancient winter spirits (big Hogfather vibes).

Funnily enough, I was “attacked” three times – twice by the Devils from Luzón Diablos de Luzón. They paint their bodies black and carry cowbells on their belts, horns on their heads and big teeth made from potatoes – they painted my forehead and jawline black in two different occasions. Another time, one of the Vaquillones from Robledillo de Mohernando Vaquillones de Robledillo de Mohernando mock-charged at me. I startled and he was mortified. But it was all good. Oh, and at some other point one of the Mascaritas dumped a handful of confetti on me – I had found a great spot to take pictures: right in front of a potted plant on main street. I was not in the way, since they had to ditch the plant, but I could take pictures of the characters up front.

Once the parade made it to Main Square, they were called by groups onto the stage. The child botarga did a little dance to show off their skills. The most impressive moment on that stage came with the exhibition of the Dancers of the Holy Child Danzantes del Santo Niño de Valdenuño Fernández. They carry batons that they use when they dance, slamming them against the batons that others carry in a very impressive display of coordination.

The speech of the major had nothing of interest, just the usual political stuff. Mementos were handed to the recovered botarga, and the guests, and then came the Proclamation to open up the Carnival period. The speaker was someone I’ve never heard of – Pepe Sanz, president of a local Vespa and Lambretta motorbikes club. I think.

Unfortunately, as I had been following the parade, I had a horrible spot in Main Square, I could not see the stage at all – but I could use my phone above my head for pictures and videos, while the people in front of me blocked the barriers and played with their phones. I can’t even. After all the speeches, welcoming the Carnival and so on, all the botargas and characters headed back to where came from. I did not stay for the backtracking, because it was cold and it was time to get back home.