My lodging in Almadén included breakfast, so I had a coffee and a toast – better than dinner the previous night, but this time there was the hotel lady working the bar. Afterwards, I just grabbed my things and redid half of my tour from the previous night, and re-visit all the spots inscribed as World Heritage Heritage of Mercury. Almadén and Idrija.

The former mining school, the first one created in Spain, Antigua Escuela de Ingeniería de Minas was still closed – it is not open to visitors due to its poor conservation state. It is a Baroque building erected in the 1780s, with a sober façade and wooden interior with basements and semi-basements to deal with the steep street outside, the whole building designed around a master staircase.

I climbed up towards the castle Castillo de Retamar. Historically, the Romans were the first to intensively exploit the mines, as they used cinnabar for pigments. Later, the Moors started distilling mercury, which they used for decoration. There are testimonies of fountains of mercury running in Al-Andalus – let’s face it, quicksilver is a fascinating thing. As the Moors wanted to protect their dominion over the mine – and the whole territory, including the water sources – they erected the castle in the 12th century. The building was later reinforced by the Order of Calatrava, but today there are only a few remains: the brick foundations of what could have been the keep, topped with a 14th-century bell tower.

I finally headed out towards the mining complex Parque Minero de Almadén. When the mine closed down in 2003, it had been the largest producer of mercury in the world throughout the current era – it is calculated that one third of the mercury used in the world comes from Almadén. The catch? Several of them, actually. First of all, mercury is toxic. Second, the exploitation of the mine was less than stellar – at a point in history, digging in the mine was a punishment for capital crimes, considered worse than being sent to row in the navy, with workers being little more than slaves. Third, the mine is surrounded by underground water reservoirs that percolated slowly into the tunnels, which reach 700 metres deep, threatening to inundate them. If breaking down rock was hard, so was carrying the mineral, along with bags of never-ending water, up and out. Since the mines closed, the water has flooded most of the 19 under-levels of the mine, rising up until the third one.

With the mine closed, life in Almadén dwindled down. The area opened to visitors in 2008. When the Unesco Heritage Declaration came in 2012, it breathed a bit of a new air into the town, turning it into a tourist destination, but lack of management makes it, in the end, barely worth a day’s visit. Visits to the mine are only guaranteed at the weekends, when the museum located in the university is closed down. Reservation of activities is confusing, and unless you’re a whole group there is no way to book a complete visit. I had booked the guided visit to the mine at 10:30 in the morning and a visit to the museums in the afternoon. I was not sure that I could do both before Spanish lunch time, but figured out I would be able to talk my way into the museums early if both things could be combined in one go. It was actually the cashier’s idea to have me do so, even better. One of the museums was closed and there was no warning about it anywhere but Google Maps, which feels a bit like cheating.

The main entrance to the mining complex Parque Minero de Almadén is locked down. There is a side building with an open door and a sign reading “we don’t have any information about tourist visits”, which leads to the Visitors’ Centre. That was confusing. As I came in, there was a large group who had not booked in advance because they were afraid they’d feel claustrophobic, and now they had no tickets. The cashier managed to fit them into the afternoon visit. I talked to him about my bookings and he told me to go to the museums after my mine visit, and to wander around while the rest of the group came together.

Of course, there was a family with young children absolutely in the wrong mind frame to get into a poorly-lit underground tunnel for a couple of hours. Fortunately, there were two groups organised and I made sure to insert myself into the child-free one. I didn’t want a repeat of the Cueva del Viento, where a bunch of information was lost due to kids being kids. And I understand that kids are kids but… for me it’s hard enough to focus on the information from a guide without the added distractions.

The visit into the mine only goes down to the first floor and an upper sub-gallery, after which you ride out in the “mining train”. Before starting, you need to get your helmet, and some lanterns are dealt out to each group to improve visibility in the tunnels. The rules are simple: distribute the lanterns throughout the group, keep light pointed at the floor. Apparently, those pointers are too hard to follow – my group had three lights together in the middle of the group, pointed upwards all the time. Good thing phones have torches now.

The descent to the mine is done through a modern-times lift installed in a former shaft Pozo de San Teodoro, down 50 metres to the gallery. It did not feel claustrophobic to me, and surprisingly, I was more impressed about knowing about the water creeping up than the rock above my head. The visit took about two hours and a half. Along the walk we saw areas that were worked on from the 17th to the 19th centuries, along some of the machinery that came into play in the 20th.

Don’t get me wrong, back in the day mining those tunnels must have been beyond horrible. It is impossible to describe the history of mine without considering the harsh conditions the workers had to endure, especially the prisoners that were all but enslaved there for decades. The most intense exploitation of the mine happened during the age of the Spanish Empire and its expansion to America. Mercury became a key ingredient in the production of gold and silver in the New World.

Throughout the works in the mine, various exploitation strategies were used, digging both horizontally and in angles. We saw different methods and tools, from plain old pickaxes to modern hydraulic hammers, and the room where the mules would work to help extract the cinnabar. We were shown corridors held up by wooden beams – which were discontinued after in the mid 1750s there was a fire that lasted two years – and later brick ones. We saw shafts that had water at the bottom, and in the end we rode a little mining train to come up to street level. The visit ended with a brief lookout and explanation of the furnaces used to purify the mercury.

Afterwards, I had my visit to the museums. One of them has an explanation of the mining procedures, the same thing we had heard within the mine itself. The second held the former workshops, which displayed machinery to keep up with the maintenance of all the apparatuses used within the mine. I was the only person who had booked those tickets, so it was a quiet visit. I was also allowed to amble around the outer part of the mining park, seeing all the heavy-duty machines.

I left the mining park and tried to find the historical gates. The entrance to the mines has always been walled off – historically to protect the valuable resources it held. I could see the restored Puerta de Carlos IV. This gate would have taken me to the Mercury Museum, currently closed. There was another gate, but the overgrown vegetation made it impossible to do more than glimpse it.

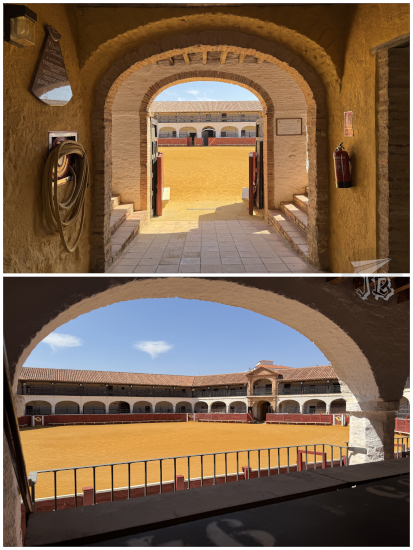

My next step was heading back downtown until I reached the bullfighting ring Plaza de Toros de Almadén. During thirty-month fire of the mine, which started in 1755, the miners had to work on anything, anywhere, to raise some money. One of their ways to get income was converting the communal garden into a bullfighting ring – at least that is one theory. Today, it is considered the second-oldest ring in the world, with the characteristic that the coso (the actual bullring) is not a circle but a hexagon. It is an important national monument and part of the Heritage Site.

In front of the entrance to the bullring stands the Monument to the Miner Monumento al Minero, which takes a new meaning after having visited the mine itself and heard about all the hardships and dangers within its galleries.

And then came the hard job to find a place to grab a bite. I wanted to try a typical dish from a restaurant with a typical name, but they had run out… For real. At least they let me have lunch at the bar… It made me decide to buy something from the local supermarket to have dinner later on. After lunch, I went back to the hotel to wait for 17:00, when the last monument would open.

This was the former hospital Real Hospital de Mineros de San Rafael. It was built between 1755 and 1775 – started during the fire – in order to treat miners who became ill or had an accident in the mine. The most common malady was hydrargyria – mercury poisoning – though of course there were physical accidents, especially loss of fingers after dynamite was introduced.

The visit has three parts of sorts. On the right there is a bit on the history of mining medicine and mercury poisoning. On the left, a very humble display of what is called “the archive” – documentation related to the mine and mining operations. Upstairs, a ward with some archaeological items and an exhibition about how the layman lived outside the mine, with a chilling panel explaining that the work in the mine was considered so dangerous that children would not be allowed to play when there was a relative in the galleries.

Afterwards, I moved towards the current university, which has been built around and over the former prison Real Cárcel de Forzados, but there was nothing to see from the outside, and the campus was closed as it was a weekend. However, I was on a small hill, so I decided to continue upwards and see if I could get a general view of the mining park. I ended up at a small forest-park, but did not get a great view.

I headed downtown again and I headed towards a tobacco shop I had seen in a small side street. They had souvenirs in the window, so I hoped that they would sell some mercury. Technically, you cannot buy mercury in Europe – both the Mining Park and the Hospital staff had told me so – but this little shop had a little for sale. So yay me, now I officially own some Almadén mercury.

I found the side entrance to the church Iglesia de Santa María de la Estrella, but no other shops open – I wanted to buy some local cheese. Not even the supermarket had anything that I would not find in my local one. I did buy some dinner and snacks though, and a thermally insulated bag because mine is old and is not working that well any more. It helped keep dinner fresh until I reached the hotel and could use the small fridge there. Pity about the cheese though.

I turned in afterwards to decide what I would do on my way back, and study the routes.