I woke up and for the first time in days I put on “person clothes” (for the city) instead of “scarecrow clothes” (for hiking & working in the field). Before setting off on the trip, I went to the sales to buy some jeans that would work for sitting on rock or walking through thistles and dry grass, and while they are not particularly nice, they are comfortable and resistant. Saragossa / Zaragoza was still waking up as I headed for breakfast to a bakery close to the hotel, Pannitelli Original Bakery, which I had chosen for two reasons. One, they opened at 7:30, which gave me plenty of time to walk to the university afterwards and two, they had waffles, I had seen them online. I wanted waffles, and a big coffee. I had both (and some orange juice, just because I could).

It turned out that not driving to the university Universidad de Zaragoza had been a great idea. Though it had been my first thought (dump the car there, then walk to my accommodation), I was lucky that in the end I was able to reserve my parking spot with the hotel. It happens that access to campus is restricted to working staff. Students can drive into the parking lot ten times in the school year. And on top of that, there was a farmers’ market for some reason.

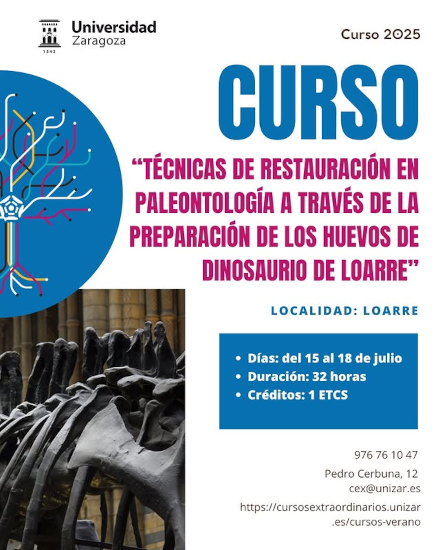

Having 20 minutes to walk, I was the first one there, and I sat down in the rock garden of the Earth Sciences building to wait for everyone else for the last day of the course Técnicas de restauración en paleontología a través de la preparación de los huevos de dinosaurio de Loarre: Palaeontological Restoration Techniques through the preparation of Loarre dinosaur eggs. By 9:00, when class was to start, I was the only one besides the teachers who had managed to arrive. Everyone else had either got lost, left Loarre late, or was taking forever trying to park. So yay me being lucky for once (and for the 20 € which the hotel parking cost for the whole stay).

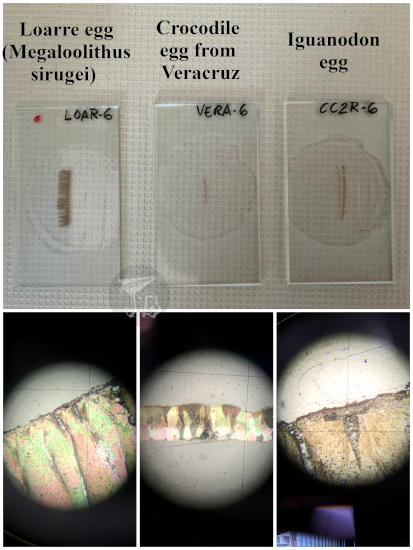

The first chunk of the morning was a tour through the Rock and Hard Material Preparations, 3D Printing and Scanning Service (Servicio de preparación de rocas y materiales duros, impresión y escaneado en 3D) in the university. They have two main lines of work. One is to make thin translucent sections out of specimens so they can be studied under the microscope, and the other is digitalising and making 3D models and copies of items so they can be lent or studied through a computer. The inner works of the department were explained by Raquel Moya Costa, who not only described in detail all her complex machinery, she also gave each of us a 3D printed T-Rex charm from the Dino Run Game!

We then moved onto the Petrology lab to look at thin sections on the transmitted-light microscopes – preparations of a sauropod eggshell, a crocodilian eggshell and an iguanodon eggshell. There were other preparations we could snoop around if we promised not to take pictures and publish them. We also got to play with the 3D copy of one of the first eggs recovered from Loarre. Much less heavy than the real thing, for sure.

Then a bit of chaos ensued as we got distracted by the shiny exhibits of the Palaeontology department, and a couple of post-docs offered to show us their lab and what they were working on. Having finished all the activities of the course, the coordinators had organised an extra visit to the Natural Science Museum Museo de Ciencias Naturales de la Universidad de Zaragoza (which might have actually been my fault as I asked how come that would not happen, considering that most of the region’s fossils are officially deposited there). A few people left first, but some of us got delayed looking at the lab specimens, and then we had to hurry to the museum…

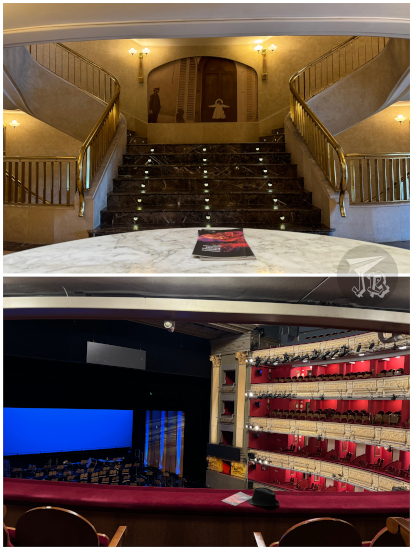

Once we were at the site of the Museo de Ciencias Naturales, we were taken on an express visit of the palaeontology ward by Ester Díaz Berenguer, curator of the collections. The museum is located in one of the historical buildings of the Zaragoza campus. Designed by Ricardo Magdalena in 1886, it was erected with academicist criteria, in brick, with large windows and striking symmetry. It opened in 1893, and during the 20th century, it served as Faculty of Medicine. When the university moved to the newer campus, the building was refurbished as cultural spot and seat of the government body. The basement was turned into the exhibition site of the Science Museum, which has three main areas – palaeontology, natural science, and mineralogy.

The palaeontology ward of the museum comprises nine rooms. The first one is an introduction to the science and the concept of fossilisation, and the following ones run through the Earth’s history, from the Precambrian to the Quaternary. The Precambrian is the earliest “calculated” period in geological time, and spanned from 4567 to 539 million years ago (give or take). Though we cannot pinpoint when life actually originated, it was already there when this “supereon” gave way to the Cambrian. During the Ediacara Period, at the end of the last Eon of the Precambrian, the Proterozoic, the earliest complex multicellular organisms that we know about thrived in a state that has been called “The Garden of Ediacara”. The word “garden” tries to evoke the idea of the “Garden of Eden” as there was no active predation and life just… existed.

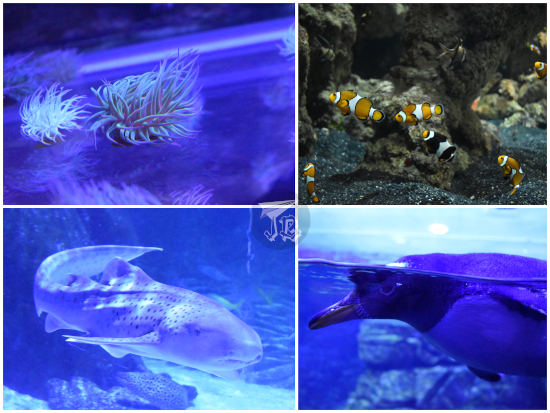

The next rooms focus on the “Cambrian Explosion”, a term used to refer to the point in geological time when living things took over the planet. At first, this brand-new life was comprised of ocean-dwelling invertebrates. In the room there are impressive trilobites from the Murero Palaeontological Site, which I had actually planned to drive through on my way back. But not only animals appeared, so did plants – organisms which produced a new toxic gas that would change the planet forever: oxygen. To the side of this area there is a curtained room, the “aquarium”.

Here you can see the cranium of Carolowilhelmina geognostica, a fish which lived around 392 million years ago, during the Devonian period. It was a placoderm, a group whose main characteristics were being covered in armoured plates, and having developed an actual jaw and true teeth. The specimen is not just the holotype, it is the only known fossil of the animal. The cranium alone measures almost 45 cm, and by its shape, palaeontologist speculate that the animal was probably a predator of invertebrates. A first fragment of the fossil was found in Southern Aragón in 1971 by palaeontologist Peter Carls. Carls kept returning to the site to search for the rest of it every summer, until in 1986 he unearthed the rest of the skull, which was finally extracted in 1993.

The following room is devoted to the Mesozoic, and it hosts another of the museum treasures, the skull of the holotype and only specimen of Maledictosuchus riclaensis, the “Cursed Crocodile from Ricla”. This crocodilian lived in saltwater around 163 million years ago, during the Middle Jurassic. It had flippers instead of legs, and probably ate fish. The fossil was found during the construction of the high-speed railway between Madrid and Barcelona in 1994. It earned the name of “cursed crocodile” because despite the fact that it was the oldest crocodilian found in Spain, exceptionally preserved on top of that, it took 20 years until someone could tackle its study and description. The “curse-breaking” researcher was Jara Parrilla Bel, one of the post-docs who shown us her lab work at the university.

Of course, the “stars” of any palaeontological exhibit are dinosaurs. The museum hosts several iconic pieces, amongst them replica of the feet of the first dinosaur ever described by researchers belonging to the local university Universidad de Zaragoza, Tastavinsaurus sanzi (a titanosaur), a whole specimen of the Mongolian Psittacosaurus (a small ceratopsian), and a good part of an Arenysaurus ardevoli, a hadrosaur which lived in the Pyrenees area around 66 million years ago, during the early Maastrichtian; the rest of the specimen is located in Arén, where it was located, and which is one of the museum’s satellite centres, just like Loarre’s museum-lab. In the same room there were trunks of fossilised wood that could be touched, and a skull of the extinct crocodile Allodaposuchus subjuniperus.

After a small room with an audiovisual representing the impact of the meteorite and the K-Pg mass extinction (which we skipped due to time constraints), there was an exhibit of the spread of mammals. The specimen of honour in this exhibit is the ancient sirenian Sobrarbesiren cardieli (holotype, and the topic of our guide’s thesis). This species lived during the Eocene, around 45 million years ago. Sirenians (manatees and dugongs) are a type of marine mammals whose closest relatives are elephants – and not other ocean-dwelling mammals. After life spread through land, a number of mammals went back to water, and it looks like this species is a snapshot on the readaptation process: it was already completely aquatic, but it still had four functional limbs. Its hind legs had started reducing and its tail was getting flat. It was a strict herbivore, eating sea grass, but less efficiently than current sirenians.

There was also an impressive aquatic turtle of the genus Chelonia, several remains of Gomphotherium angustidens, an elephantimorph, and smaller pieces including crabs, sea urchins, gastropods and even insects. Several of these specimens are holotypes, too.

The final area was almost contemporary considering when we had started. It hosted remains of cave bears (Ursus spelaeus, 40,000 years ago), the skull of an aurochs (Bos primigenius, a species that actually lived until the 1600s), evidence ancient hyena nests, micro-invertebrate bones, mammoth defences… These animals coexisted with human beings, whose skulls comprise the ending room before moving onto the “nature collections” which we did not visit because a) the course had after all to do with palaeontology and b) it was closing time – quite literally, museum security was turning off lights behind us since the museum shut down at 14:00.

We had a mini closure “ceremony” in the hall of the building – coordinators Miguel Moreno Azanza and Lope Ezquerro Ruiz thanked us for attending, we clapped and thanked them back. Then we all went off to have a drink, a snack and a chat. A bit after 16:00, when most students had already left and the professors had been joined by university staff, I took my leave.

Hopping from shadow to shadow to avoid the sun and the heat as much as I could, I headed downtown. On my way I made an exception regarding the walking in the shade when I found the only remaining gate of the original Medieval Wall, today called Puerta del Carmen. Calling it “original” is a bit of a stretch though. While it is in the same place as the first gate, it actually dates from the early 1790s, and it follows Neoclassical patterns.

I also stopped at Starbucks for a Vanilla Frappuccino – I’m on a bit of a matcha remorse trip due to the alleged shortage, so I’ve reverted to my old drink of choice. With a temperature of around 38 ºC, I reached the most important square in town, Plaza de Nuestra Señora del Pilar, where the namesake basilica is. I kid you not, what was running through my head was “I’ve got a 0.5 zoom on my phone now, I’ll be able to take a nice picture of the whole building with its towers…”. Only to find said towers covered in scaffolding. I was able to take the picture, but it could have been nicer. I entered the Cathedral-Basilica of Our Lady of the Pillar Catedral-Basílica de Nuestra Señora del Pilar, a Baroque / Neomudejar catholic temple which is considered the first-ever church dedicated to the Virgin Mary. I sat at the chapel for a little bit, but when I was ready to have a walk around the church, there was a call for mass, so I did not do it out of respect.

Instead, I strolled to the former exchange building Lonja de Zaragoza, which has been turned into a free exhibition centre. The building is Renaissance with a touch of Neomudejar, and it is considered the most important civil architecture construction erected in the whole area of Aragón during the 16th century.

I had read that there was an exhibition on Asian culture called Tesoros. Colecciones de arte asiático del Museo de Zaragoza – Treasures: Asian art collections from the Zaragoza Museum. At the moment, the Zaragoza Museum is closed and has loaned a few of its artifacts to be displayed elsewhere. This one exhibition displays items that were originally part of personal collections and were donated to the museum. The Colección Federico Torralba, comprises religious items and art pieces from China and items from Japan. The Colección Víctor Pasamar Gracia and Colección Miguel Ángel Gutierrez Pascual have woodblock prints – landscapes, noh [能], kabuki [歌舞伎], even modern ones. The. Finally, the Colección Kotoge displays lacquered tea bowls (chawan [茶碗]). There are also modern calligraphies, paintings, and the compulsory samurai armour. The regional government has undertaken buying artefacts to engross the Asian collections. Though they looked a bit out of place in the historical building, the items were fantastic – and you could even make your very own “woodblock print” at the end.

Though the exhibition was the reason I had wanted to go downtown, after I left the (nicely air-conditioned) Lonja, I still had some time to do stuff. I wandered back into the cathedral for a bit – between the 17:00 mass and the 18:00 mass, and left before the second one started.

I continued towards the Roman Walls Murallas Romanas de Zaragoza, which sadly have had to be fenced off because people have no respect (I vividly remember a mum letting her toddlers to climb all over them one time I visited). At the end of that square stands the marketplace Mercado Central de Zaragoza, a wrought iron architecture building designed in 1895 by Félix Navarro Pérez. Being a Friday evening, in the middle of summer, many of the stands were closed, so it was not crowded.

I continued towards the Fire and Fireforce Museum Museo del Fuego y de los Bomberos, where a nice gentleman wanted to give me a guided visit which I declined. Honestly, I just wanted to look at the old fire trucks (and actually, support any initiative by firefighters if it helps fund firefighting). It is a little quaint museum located in part of a former convent, the other half is an actual fire station. The exhibition covers documentation of historical Zaragoza fires, firefighting equipment, a collection of helmets, miniatures, and quite an impressive collection of vehicles used to fight fire. There were two immersive rooms, one which showed damage to a house and another about forest fires. I really enjoyed it, though I only had a quick visit – they closed in an hour, and I was the only guest along a family.

On my way back towards the hotel I walked by CaixaForum Zaragoza, where they were running the Patagonian dinosaurs Dinosaurios de la Patagonia. Seeing the Patagotitan on the balcony made me want to go in, but I had already seen it, and I knew I was just on a palaeontology high.

I headed back to the hotel – crossing a couple of quite unsavoury neighbourhoods – and bought some fast food dinner again. It was stupidly early, but after eating I could have a shower and relax on the bed while I studied the route for the following day. Furthermore, it was so hot I really needed that shower, and I knew I would not be going anywhere after taking it. Thus, I showered and plopped down to watch the Natural Science Museum’s YouTube Channel after I had learnt how to get out of the city.