Mount Fuji aka Fuji-san [富士山] is a special mountain in Japan, both geologically and culturally. Japanese and tourists enjoy Fuji-san in different ways – contemplating it, visiting it, climbing it, going around it… Well… Guess who got into their thick head that they wanted to climb it? raises hand Exactly! Yours truly. I was already toying with the idea back in 2018, but I chickened out. However, as I mentioned before, this one time I wanted to scratch as many things off the bucket list as possible, so… There I went – kinda pushed by a feeling that if I did not do it, by the time I were back in Japan it might be too late as my health is not.… complying lately. But I had not hiked up a mountain before in my life…

Mount Fuji is the most famous mountain in Japan. Its iconic image is everywhere – enamel pins, t-shirts, postcards, classical art… Located around 100 kilometres south-west of Tokyo, it is 3,776.24 metres high, which makes it the highest peak in the country. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2013.

Technically, Fuji-san is neither a mount nor a mountain, but a type of volcano known as a stratovolcano. Its current morphology was shaped by consecutive layers (“strata”) of lava hardening. It is mainly composed by a rock called basalt, and it is one of the few large basalt volcanos in the world. Basaltic lava is rather thick and slow-moving, so there are many lava tunnels and tree moulds created by the eruptions.

Fuji-san, as we know it today, was formed from a previous volcano (Komitake), and became active around 5,000 years ago. Around 2,300 years ago, there was a mud landslide (Gotemba mud flow [御殿場泥流, Gotemba deiryū]) that can still be identified. There have been several historical eruptions, twelve of them between the years 800 and 1083. There was a ten-day eruption of ashes and cinder in the year 864 (Jōgan 6 in the Japanese calendar, based on the different Emperor’s reign; 2019 is Reiwa 1, as current Emperor Naruhito just ascended the throne). In the year 1707 (Hōei 4 in the Japanese calendar), a few weeks after a big earthquake, the last known eruption took place. In the current Japanese Volcanic Alert Level, Mount Fuji is categorised as “Level 1: Potential for increased activity”, which is the lowest level.

Mount Fuji has frequently been depicted in Japanese art, most famously in Katsushika Hokusai’s [葛飾 北斎] Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji [富嶽三十六景, Fugaku Sanjūrokkei] by, a series of ukiyo-e block prints (which are actually 46). Probably the best known among these is The Great Wave off Kanagawa, one copy of which is displayed at British Museum in London (actually, in 2017 they ran a whole exhibit around it and Hokusai).

Fuji-san is also an important element in the collective spirituality of Japan. In Shinto mythology, the goddess of Mount Fuji is Konohanasakuya-hime [木花咲耶姫]. She is enshrined in Fujinomiya town Fujisan Hongū Sengen Taisha [富士山本宮浅間大社]. Technically, this shrine has owned Mount Fuji since 1609, though there are no current records of ownership. The volcano stands at the boundary between the prefectures of Shizuoka and Yamanashi, and in order to manage the natural area, the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park [富士箱根伊豆国立公園, Fuji-Hakone-Izu Kokuritsu Kōen] was established.

Depending on the actual weather, Fuji-climbing season extends from late June or early July to early September. It is not allowed to climb Fuji “off-season” without a permit. However, people do not usually climb the whole mountain, but start quite closer to the summit. There are roads leading up Mount Fuji up to around 3,200 metres, to an area called the Fifth Stations However, no private cars are allowed on those roads.

From the Fifth-Stations there are four trails or paths to the summit, colour-coded to help people find their way, especially on the way down:

- Yoshida Trail [吉田ルート] (yellow). It starts at the Fuji-Subaru Line 5th Station [富士スバルライン五合目] (Yamanashi Prefecture). This is the trail recommended to “beginners” and thus the most crowded.

- Subashiri Trail [須走ルート] (red) Head. It starts at the Subashiri Trail 5th Station [須走口五合目] (Shizuoka Prefecture).

- Gotemba Trail [御殿場ルート] (green). It starts at the Gotemba Trail New 5th Station [御殿場口新五合目] (Shizuoka Prefecture).

- Fujinomiya Trail [富士宮ルート] (blue). It starts at the Fujinomiya Trail 5th Station [富士宮口五合目] (Shizuoka Prefecture).

When I told D****e that I was planning to try to organise the climb, she did not believe me at first. As she realised I was being serious, she decided that she was crazy enough to want to come with me as “she could not let me do such a thing alone” and actually took over most of the planning, since she had done it before. I would have just found an agency, but I think she was better.

So off we went. As she was working, we organised our hike on a Saturday-Sunday trip weekend trip – and we did not realise until afterwards that we would be climbing during Mountain Day – Yama no Hi [山の日]. We packed snacks, water, and everything we thought we might need – in my case, also gloves which I eventually lost, and a ridiculous amount of layers. D****e was chill, but I was a little worried about all the equipment the Official webpage for Mt. Fuji Climbing said that was needed, including oxygen and helmets. There were also warnings in place, such as your mobile phone battery dying super-fast, or the need for an evacuation plan in case altitude sickness got too much. I was also worried about weather (especially rain) and temperature changes – thus all the layers. She insisted we would be fine.

After a big lunch, we took the Shinjuku Expressway Bus around 16:00 on Saturday the 10th, and arrived at the Fuji Subaru Line Gogōme [富士スバルライン五合目] / Fuji Subaru Line 5th Station at 2,300 m around 17:30. We (she) had booked a mountain hut at the Seventh station so we “only” had to climb two stations, right? Right. Read: wrong.

Right about the time of taking this picture it had sunk on me how much of a bad idea this had been (≧▽≦). I really wondered if it was too late to turn back and go home.

My first step was buying a staff – that we nicknamed the “Fuji-climbing stick”. The idea is that you use it to feel your way around and make sure that you step on solid ground, and especially when you hike down. However, (you’d never guess), you can get stamps burnt into the wooden stick as you hike up – usually for 300 ¥. Climbing Fuji can get expensive… D****e had chosen the Yoshida Trail [吉田ルート] for our ascending side (noborigawa [登り側]). And so… off we went.

We started off climbing at around 18:00. Between the Fifth (2,300 m) and the Sixth Stations (2,390 m), you walk along some dirt paths in the forest, and there isn’t really that much “ascension”. As there was also light, the first hour was easy enough. This area is crowded due to all the “visitors” going for a “walk” from one of the Fifth Stations to another. We actually saw someone using up their oxygen at this point. That was weird.

From the Sixth Station there was a first zig-zag upwards, with paths held up by some dams. This is one of the parts I found the hardest, as it is the same inclination all the time and I was not warmed up yet. Then, sunset came, and while it was pretty, it brought darkness upon us (yeah I’m being literary on this). Not that I had a problem with actual darkness, but other people’s torches and headlights kept blinding me, which made the most difficult parts hard to climb – because some people are idiots who point their lights forward and not downwards, where the ground is. Sheesh. There were parts that were just a gentle incline up, while others were stuck rocks or lava flows that you had to climb with your hand and feet.

At the Seventh Station (2,700 m), the path changed and we started. Though there were some slopes, there were also stuck rocks and lava flows that I had to climb with my hands and feet. Fortunately, I could make use of the short stops we made to stamp my staff. Workers of the Mountain Huts use hot irons to burn the stamp into the wood. I think I got all the ones I could on my way up (no stamps on the way down).

Mountain huts [富士山の山小屋, Fujisan no yamagoya] are tiny establishments where you can get some food or spend the night for around 10,000 ¥. They often require reservations, usually in Japanese, that is why D****e took charge of that part. Some of them have a bin for rubbish – because you can’t dispose of trash on the slopes, you have to take back what you brought in. They have toilets too, and require a tip. Most of them follow an “honour system” with a small coin box, but some have a guardian to collect the money.

We continued upwards until we made it to our Mountain Hut, Shichigōme Torii sō [七合目 鳥居荘], the Seventh Station’s Torii-so at around 21:00. We had been told it was the one with the red torii, and it was a sight for sore eyes. It stands at 2,900 metres high, closer to the Eight Station than the Seventh – we had expected to find it sooner due to the name.

D****e had booked a bed and a meal. As we came into the hut, our staffs and backpacks were hung over the door, and we were given bags for our shoes and personal effects. We had a small riff-raff with the owners, because they claimed that we had arrived too late for food. However, D****e argued that the webpage said nothing about a time limit. Thus, we got some curry and rice as the dinner we had booked.

Around 22:00, we used the toilet, and then we were shown to the common dormitory – the bed bunks are basically a line of futons put together so you share a blanket with the person next to you. The idiot I had to share with decided to lie on the blanket instead of under it, so she had me uncovered half the time until she left.

Thankfully, at around 23:00 there was a call for people who wanted to set off in time to see sunset from the summit, and she got going. Between getting uncovered, and lying down too soon after food, I started feeling queasy. I freaked out a little. I started turning in my head that I was going to get sick and not get to the summit and have to be evacuated. D****e helped me calm down and I managed to get a few hours of sleep.

But just a few. We were woken up by the noise around us around 4:15. I felt strangely not tired, and D****e indulged me. Thus, we got up and went outside to see sunrise. Sunrise from Mount Fuji!!! I mean… I can’t even. Unfortunately (and ironically) we left too early to get the stamp from our own hut! We continued our way and had breakfast at the next big rock where we could sit down.

After coffee (yes, I’m addicted enough to carry coffee to Mount Fuji), we went on hiking. To be honest this second day was not as bad as I had imagined – as in I was rather convinced that I was not going to be able to make it, especially during the night freak-out. My painkillers kicked in and I only felt a small buzz in my ears as pressure changed.

It did not take too long to arrive at the New Eighth Station (3,100 m). Once again the trail became irregular, which on one hand was tiresome, but at the same time, it was not tedious, so it did not feel as hard. Gloves were useful for this part of the hike, as I could hold on to things. We continued up to the Original 8th Station (3,400 m).

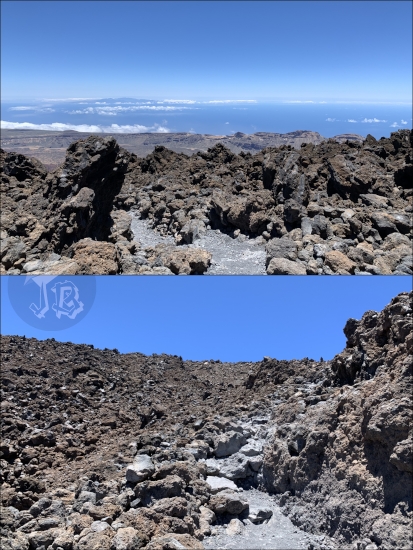

After the Original Eighth Station the trail became path-like again, with torii and stairs and fewer rocks you had to climb over, but a bunch of smaller ones that you had to step up on. Here I learnt to appreciate the actual usefulness of my staff. Vegetation disappeared gradually until the ground was barren.

I think I lost my gloves at the Ninth Station. We saw a group of people evacuating an injured / ill climber – we mentally awarded them like a million karma points, and after getting the injured person to help, they happily went back up again. One of them told us their group does it every year. I remember hugging some torii on the way, and a thousand thoughts twirling in my head.

And then we made it. Around 11:00 we reached the rim of crater. I could not believe my own eyes when I stepped in front of the shrine Asama Taisha Okumiya Kusushi Jinja [淺間大社 奧宮 久須志神社] and Fuji-san Chōjō Yamaguchi-ya Honten [富士山頂上 山口屋 本店] aka Top of Mt. Fuji Yamaguchi Shop. I had made it. I had beaten my own limits, and reached the crater.

Of course I needed to get all the stamps and the shuuin and the exclusive Coca-Cola bottle. We decided not to go around the crater to the highest point, just a handful of metres higher, because it would add some 90 minutes to our trek, and we preferred to just hang around where we were for that long. Because I was at the freaking crater of Mount Fuji! I was the Kami of the Mountain.

Walking around the crater would have been great, but we would be hard-pressed for time for our bus if we took too long. D****e asked me what I wanted to do, and I was happy staying around the crater taking pictures and enjoying the feeling. After an hour or so, we set on our way back down – the trail was a bulldozered zig-zag of gravel, boulders and volcanic sand, and it was even more exhausting than the way up.

It was tricky not to slide and fall. It took us about three hours until we were back to the forest area and the Sixth Station. We reached our Fifth Station around 15:30. I did not fall even once – thank you, Fuji-climbing boots from the Decathlon Children Section for not letting me down, literally!! I also acknowledge that we were super-lucky with the weather, we only had a few clouds just under the crater, and it was not too cold even for me – and no rain, which would have made the experience miserable.

We actually made it with some time to catch our bus, so we looked at the souvenir shops and Fujisankomitake Jinja [冨士山小御嶽神社].

As we left, we could see Mount Fuji in all its glory, and I could not believe that I had actually been up there! The total experience had taken a bit over 27 hours, and it was exhausting but exhilarating.

However, the downfall had to come, and it came in the bus, about 20 minutes into the ride home – once I stopped moving, my body completely shut down in pain. My back cramped, headache hit, left knee got stuck, and the road trip was horrible. I did not want to have any dinner even if I knew I needed it, but a hot pot in the conbini managed to draw me and it was exactly what I needed!

Walked distance: 10th: 9988 steps / 7.14 km; 11th: 21107 steps / 15.1 km. However! The damn watch does not take into account that I CLIMBED A VOLCANO!! I mean, come on! Some of those steps had a 70 cm difference in height! I managed to do it, and I feel damn proud of myself for it, and I will forever proudly display my Fuji-climbing stick as proof of the feat. Also, just so you know 11th of August is Yama no Hi [山の日] (Mountain Day) so this was ironically well-timed, even if by pure chance!

I know that hundreds of people climb Fuji-san every year, but for me those almost 3,776 metres represent something special. It was my very own challenge, something I never thought I would be able to do, and yet I managed. I was extremely proud of myself. I think it helped me become more adventurous, as I found out that I could really push my limits. There was a price to pay afterwards, yes. But I had made it and I don’t regret it (I did regret it a bit the following day going down the stairs though. But not much). I was the Kami of the Mountain.