I am not a big fan of musicals – not because of the genre, but because in general the stories don’t seem to appeal to me. However, I like Wicked. Just before the first instalment of the movie duology was released, it was announced that the musical was getting a Spanish version. I was on the fence as to whether buy tickets or not, because I have often come across horrible translations into Spanish. After a lot of pondering, I decided to get an opening-day ticket, which I purchased in late November 2024. If in the end I backed up from attending, I could always give it to someone else, as it was sure to be a full house. Thus, I got a spot for Wicked: El Musical in Nuevo Teatro Alcalá in Madrid. However, once the film was released and I got to read the subtitles – I’m a visual person, I can’t ignore subtitles no matter how much I try – I became a bit more apprehensive.

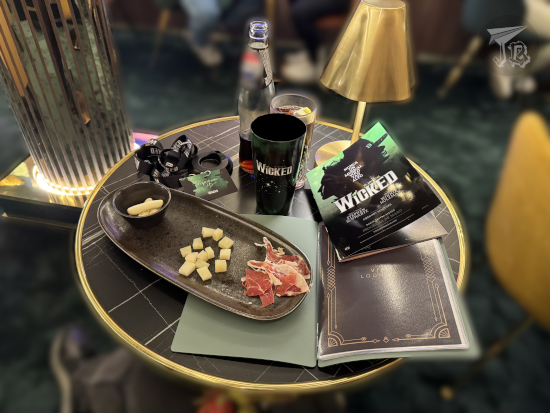

In March 2025, I received an email advertising the option to get a VIP upgrade, Experiencia Premium Wicked, which included early entry, the booklet, a guided tour of the theatre, and what was de-facto dinner in the VIP lounge (which had its own private toilets). It was convenient, so I purchased it. Since I had originally bought the ticket on presale, some kind of discount was applied to it. I can’t be sure how much due to the anything-but-transparent Spanish ticket pricing. The nice seat on row 13 had a face value of 84.90 €, there was a fee of 6.79 € and a discount of 17.98 €, yielding to a final price of 74.71 € for the seat. The Premium upgrade was 29.90 €, value for money for the convenience only. Thus in total, I paid 104.61 €, without even being sure I was going to attend – I think my nibling was praying I would back out in the end and gave them the tickets…

I was not completely sure what to do with myself that day. I got a hotel because the 21:00 session would wrap up late, especially on opening day. The theatre Nuevo Teatro Alcalá was not in a convenient point to drive to. Trains would not be running any more when I reached any station, but the underground would. The only affordable but private room I found was 20 minutes away on said underground, but a big city would still have reasonably-full trains around midnight on a Friday in what is climatologically late-summer. The hotel was relatively close to the largest cemetery in Madrid, Cementerio de La Almudena, which reportedly holds some masterpieces of funerary architecture. I thought that it being October, it might be an appropriate visit, following a cultural itinerary provided.

On the day of, I set towards Madrid so I could reach the hotel a bit around check-in time, at 15:00. I dropped my luggage and set off towards the graveyard. Cementerio de La Almudena is the largest cemetery in Western Europe. It opened in 1884, though it was officially inaugurated in 1925. There were several architects involved in the design, but the current appearance is due to Francisco García Nava, who substituted previous styles with different Modernisme trends. Looking from above, the cemetery is designed as an adorned Greek cross, a design that eventually yielded to the creation of a secondary civil cemetery across the street.

I had wanted to visit for a while, but once there, I found Cementerio de La Almudena oppressive. Though there are green areas, it had nothing on the nature feeling northern Europe cemeteries give off. The niche walls felt overcrowded and cold, and the paved paths seemed designed just for vehicles and not people. I mean, the cemetery is big enough that it has its own bus stops inside, but there was something off about it. It was not a Victorian Garden, I guess. Since I was not enjoying myself, I decided to cut the visit short. I left after an hour, and headed towards the Central District.

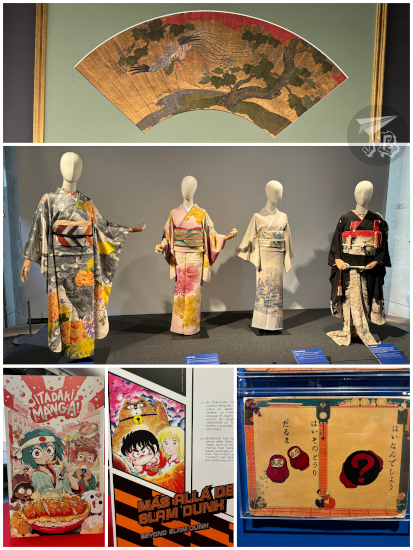

When I reached my underground stop, I saw there was a matcha bar nearby, but upon reaching it, there was long a queue outside – it turns out that it belongs to a TikTok influencer – and I decided to just go to Starbucks instead. I had a vanilla drink sitting at a park, then headed out to one of the few buildings representative of Modernisme in Madrid, the manor Palacio de Longoria. It was running an exhibition on the history of Spanish comedy cinema. I am not a fan, but exhibitions are the only way to visit the manor. The building was designed by José Grases Riera and built in 1902. It features a central staircase with a colourful skylight which is always cordoned off, but it is incredibly beautiful.

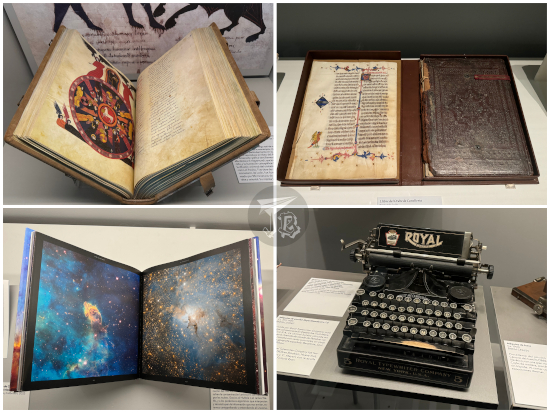

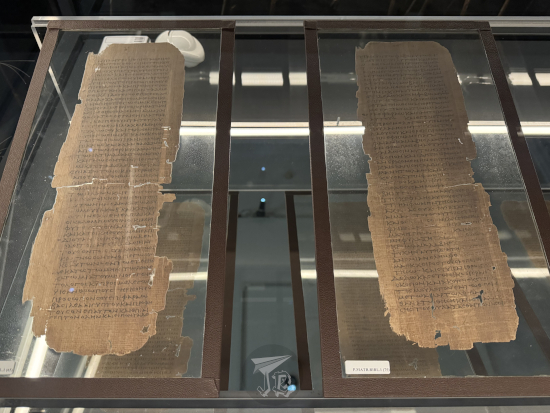

My next stop was the national library Biblioteca Nacional de España for an exhibition I wanted to see in July, but it was not running. It turns out that the temperature control in the room had broken down, and the exhibits were removed for safety. The exhibition El papiro de Ezequiel. La historia del códice P967 (The Ezekiel Papyrus. History of Codex 967) displays part of the oldest surviving document preserved in the National Library of Spain, and discusses its history. The document is a Greek translation of some of the books of the Bible, copied on papyrus probably in the 3rd century CE. It was discovered in the necropolis of Meir (Egypt), probably in the 19th century, and sold by the page to different institutions and collectors around the world between 1930 and 1950. Its excellent conservation is probably due to it being sealed in a vase until it was dug up.

The Spanish National Library is depositary of several sheets, which were originally bought by private collector Pénélope Photiadès. Upone her death, her collection of around 350 papyri, now called Papyri Matritensis, was bequeathed to the cultural organisation Fundación Pastor de Estudios Clásicos. As for the rest of the original codex, 200 out of 236 pages are accounted for in different places around the world. The pages in deposit in Madrid contain the oldest version of Ezekiel’s prophecies

The Book of Ezequiel is part of the Hebrew Bible [Tanakh, תַּנַ״ךְ] and the Christian Old Testament. Ezequiel was an Israelite priest, considered one of the 46 prophets to Israel, who lived around the 600 BCE. His prophecies or visions revolve about the fall of Jerusalem and its eventual restoration. In-between, there are prophecies against other nations or rulers who had wronged the Israelites.

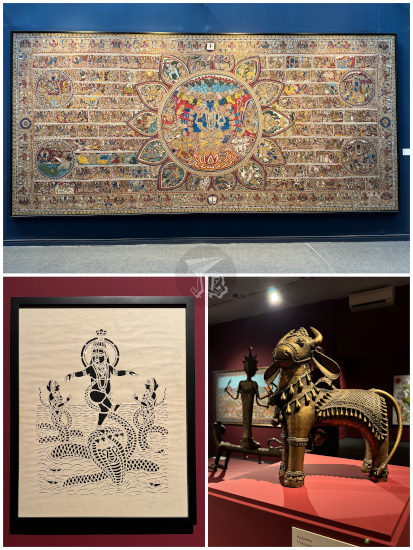

Regardless of the importance of their contents for the Abrahamic religions, it was really cool to see something that old. Especially considering that all those centuries ago, someone thought the writing was important enough to have it preserved and protected for the future. The exhibition is held in a round room, with photographies of all the known pages and their location. At the moment, there are five collections – Cologne, Princeton, Dublin, Madrid and Barcelona.

The exhibition displayed five sheets mounted over mirrors so both sides could be seen. Alongside, there are other translations of the Bible, and a small display on how to write on papyrus. The whole collection was displayed in a circular room, so it felt really immersive. It was really cool.

The weather was nice and I still had time, so I headed out to the park Parque del Retiro. This large park in the centre of Madrid originates in a Royal possession in the 15th century, and it opened to the public in 1767 under the reign of Charles III (Carlos III). Today there are several buildings remaining, alongside the royal gardens, now the large green area. There are ponds, fountains, sculptures and extremely old trees – which end up being a potential hazard when it’s too hot, too cold or too windy. This yields to quite the controversy when the park closes during summer due to the risk of collapsing branches. Parque del Retiro is considered a historical garden and part of the Unesco Heritage Site Paseo del Prado and Buen Retiro, a landscape of Arts and Sciences.

I finally headed off towards the nearby theatre Nuevo Teatro Alcalá. I ended up joining a loose group of people waiting for the theatre to open, and I got shoved away by a group coming out from a taxi. Later, one of the ladies would claim that she was there before anyone else – everyone who had seen them pushing me knew she was lying, but obviously her group needed to go in first. Ironically, though they made it to the hall first, I ended up reaching the theatre and the VIP lounge way before them. The irony.

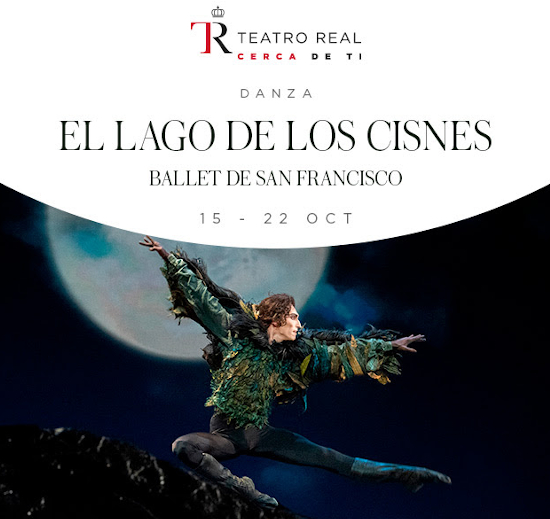

Upon entrance to the hall, I received my VIP lanyard and booklet. I am not well-versed in Spanish musical theatre actors, but I’m told the cast is really popular. First, we were shown inside the hall, where we had an introduction to the building and the play. Wicked is the musical adaptation of the eponymous book by Gregory Maguire (1995). The novel is in turn based on the world created by L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). While the original book is aimed to children – I read somewhere that it was conceived as the first “US-based fairytale”, later adaptations would take a turn towards more mature audiences.

In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a normal child from Kansas, Dorothy (with her little dog too), ends up in the magical world of Oz after being flown away by a tornado. There she partners up with a Cowardly Lion, a Tin Woodman and a Brainless Scarecrow. Together they travel to meet the eponymous Wizard, who promises to help them if they kill the Wicked Witch of the West.

The book has been both praised and reviled throughout its history. While the original story gives no room to think that the Wicked Witch is anything but gratuitously evil, the very way the protagonist party is just sent to kill her may sound… strange. It did to me when I was young and read the story for the first time. Other versions just have the Wizard tell the party to bring him the Witch’s broom.

It might have also been like that for Maguire, whose novel focuses on the evil witch, whom he names Elphaba. In the novel, Elphaba is ostracised and radicalises as she grows up, which leads to her fall into evil. In the musical, she is not really evil, but the circumstances around her life and powerful people’s manipulations make her a scapegoat. She chooses her own path rather than either give in or become a victim.

The original musical features music and lyrics by Stephen Schwartz and book by Winnie Holzman. It first opened on Broadway (after a San Francisco try-out) in 2003 – and it has run since then, except during the Covid pandemics. In 2005, it went on tour in the US, staying on different cities for literally hundreds of performances. The London production opened in the Apollo Victoria Theatre in 2006 – I have seen that one twice, in 2018 and 2022. There have been two German productions (2007 – 2011 and 2021 – 2022). There have also been runs in Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea and Brazil. Between 2013 and 2015, the first Spanish adaptation was staged in Mexico City, though I cannot be sure the translation is the same as the Mexican one. The Spain version is considered a “non-replica production” as the setting is different. For starters, there is no dragon hanging above the stage and no map of Oz on the curtain.

We did not hear any of this at the small explanation, but we learnt that they have 140 pairs of shoes. Then, we could go up the stage to get our picture taken with the giant Z on the curtain. I was amongst the first to get up there, so I also was lead to the VIP room quite early – remember the lady from before? I beat her every time, I did not even try, but it amused the hell out of me to realise it. To be honest, I had chosen the VIP experience not only because I’m a snob, but because it included what could be counted as dinner – cheese, ham and breadsticks with a drink before the play. And also the private bathroom, which was great. Ten minutes before curtain the waiters started telling us, along with taking orders for the drink during the break.

I was at my seat at 20:55, and the theatre was not full yet. The play started a little late, and I was a bit apprehensive, to be honest, because as mentioned before Spain has a less than stellar record with translations, but adaptors David Serrano and Alejandro Serrano have done a general good job. Main singers included Cristina Picos as Elphaba; Cristina Llorente as Glinda (that must have been confusing during rehearsals); Guadalupe Lancho as Madame Morrible, Javier Ibarz as the Wizard and Xabier Nogales as Fiyero. The latter was, in my totally-non-expert opinion, the weakest performance. When trying to sing with both the witches, his voice was barely audible, and he just did not have the… charm nor the presence. There is more to Fiyero’s character than choosing a cute actor, I think. There is one line that defines Fiyero in Dancing through life, which hints that there is more to him than the deeply shallow character he plays. After babbling about being brainless and shallow, when the “Ozdust ballroom” is mentioned, he sings that in the end “dust is what we come to”.

The play was well carried by the main characters, despite a couple of wardrobe malfunctions with Glinda’s dress and Chistery’s wings. The translations of the songs and the jokes were mostly on point. An exception was “magic wands, are they pointless?” – that one either completely flew over the translators’ heads, or they tried to localise it – and failed. The lyrics were well-chosen, carrying as much parallel in form and meaning as the originals. Unfortunately, the song that suffered the most was Defying Gravity, which just… can’t be easily done. It was decent though. In general, I’d give the effort an 80%.

During the break, I returned to the VIP lounge to skip the bathroom lines, and have a snack (popcorn) and my second drink. I have to say that the VIP experience is much more value for money than the London one, even if it catered to way more people – maybe because it was opening day. After the event was over, I made it to the nearby underground station and… the trains were crowded. I’ve seen fewer people on the platforms on a random weekend morning. Maybe in the future, I can drive closer to Madrid and park somewhere with an underground station so I won’t need to book a hotel.

However, staying over had a few advantages. When I woke up in the morning, I headed towards a cosy café (as cosy as a franchise can be), Santa Gloria, to order a “glorious latte with vanilla” whipped cream and cinnamon, and a salmon-on-avocado toast, which was delicious. Afterwards, I took the underground to meet up with some family members (amongst them my very-disappointed nibling). Their house is actually quite near the Museo del Aire y del Espacio, Museum of Aeronautics and Astronautics and we headed there to spend the morning.

The Museum of Aeronautics and Astronautics is a space where the Spanish Air Force preserves historical aircraft. It is located in the neighbourhood of Cuatro Vientos (Four Winds), close to the military air base. Since it was established in 1975, the site has expanded its collection to 200 aircraft. There are seven hangars full of stuff and almost 70,000 square metres of exhibition. Along with all the actual preserved items, there are reproductions of important planes in history, models, engines, uniforms… I know next to nothing about the history of aeronautics, but it was really cool to see all the machinery and even go inside a couple of planes. There were even a few items from space exploration.

We were there from around 11:00 until closing time, 14:00, and it was barely enough to have a quick look at everything. There are guides who show you around, and it might be interesting to take a visit with one of them in the future.

I had seen there was a big shopping centre nearby, but we got lost and then caught in a traffic jam, so we ended up having a very late lunch before everyone headed home for the day. Oh, but the mall had a Lego store where I could get stamps on my passport. When the salesperson asked me how many I wanted, he was somewhat surprised that I said I wanted all of them…